Doing a PhD study in Japan

In Japan people often say that its PhD system is screwed, and unfortunately I have to agree with it. At the same time, there are few Japanese pursuing a PhD outside of Japan. I couldn’t find any data on it, but I guess that they are less than 10 (even 5) % of those pursuing PhD in Japan. For instance, I was the only person, among math master students (around 40 students) at my previous university (Kyushu university) in 2020, who left Japan for a PhD.

As a rare Japanese who is pursuing a math PhD in Germany, here I want to examine Japanese PhD system (math) in comparison to German one. If you want to share the PhD system in your country, I appreciate it if you leave a comment below.

Funding

In Japan, most PhD students try to get funding from Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (日本学術支援機構). For this there are two applications: DC1 and DC2. Let me explain DC1 first.

After the first-year master studies, students who want to pursue a PhD start to write an application form of DC1. Besides basic information, they have to write (1) research proposal (3 pages), (2) self-assessment of your ability to complete the proposal (2 pages) and (3) pictures of aimed researchers (1 page). It is written in Japanese but here you can see the application form. To some degree, you have to write a proposal for any PhD application, but DC1 seems too demanding, especially for math students who just finished the first-year master study. I spent two months of writing the DC1 proposal and I always felt ‘what the hell am I supposed to write?’.

The acceptance rate of DC1 is scary: 20 %. This is not because we have many PhD students, as I will discuss later. How come a developed country like Japan funds only 20 percent of PhD students? By the way I failed DC1.

In Germany, I have never seen PhD students who are not funded. As for math PhD in Berlin, there are at least three major ways to get funding. The first is to receive scholarship from the Berlin Mathematical School. The second is to become a member of a research project. The disadvantage is that you are a part of a research project and hence you cannot always do whatever research you want to do. The third, which applies to me, is to be employed by a university through some project. In some cases you have teaching duties.

Only 20% of PhD students in Japan are funded through DC1. Many people say that whether you can win DC1 is a matter of politics and that failing DC1 does not reflect on your ability so much. Indeed, there are some researchers who now have a position in a university but could not get DC1 or DC2. Yet, failing DC1 or DC2 means a hard life due to lack of money and also has a huge adverse effect on your confidence.

If they fail DC1, they must go through the first year of the PhD without funding. They can earn by teaching assistance, but in most cases this is by far insufficient for living. Many of them end up in doing part-time jobs. However, they could get funding from the second year, if they win DC2. The format of DC2 is exactly the same as DC1, and the acceptance rate is almost the same as that of DC1.

In addition to the acceptance rate, another scary aspect is how much money winners of DC1 or DC2 receive. They receive around 150000 JPY (≈ 1040€, on Sep 13, 2022) per month after tax for living, with maximum 1500000 JPY (≈ 10400€) per year for research (e.g. traveling, buying laptop and etc). In Berlin, math PhD students receive at least 1500€ after tax per month for living, and their travels are usually covered by the funding of their supervisors. I receive around 2000€ without teaching and 2700€ with teaching. I received a mac laptop and travel costs from my supervisor’s funding.

Number and diversity of PhD students

You can find some statistics on science in Japan from this official document, based on which I will discuss here.

A more detailed information are available here but only in Japanese.

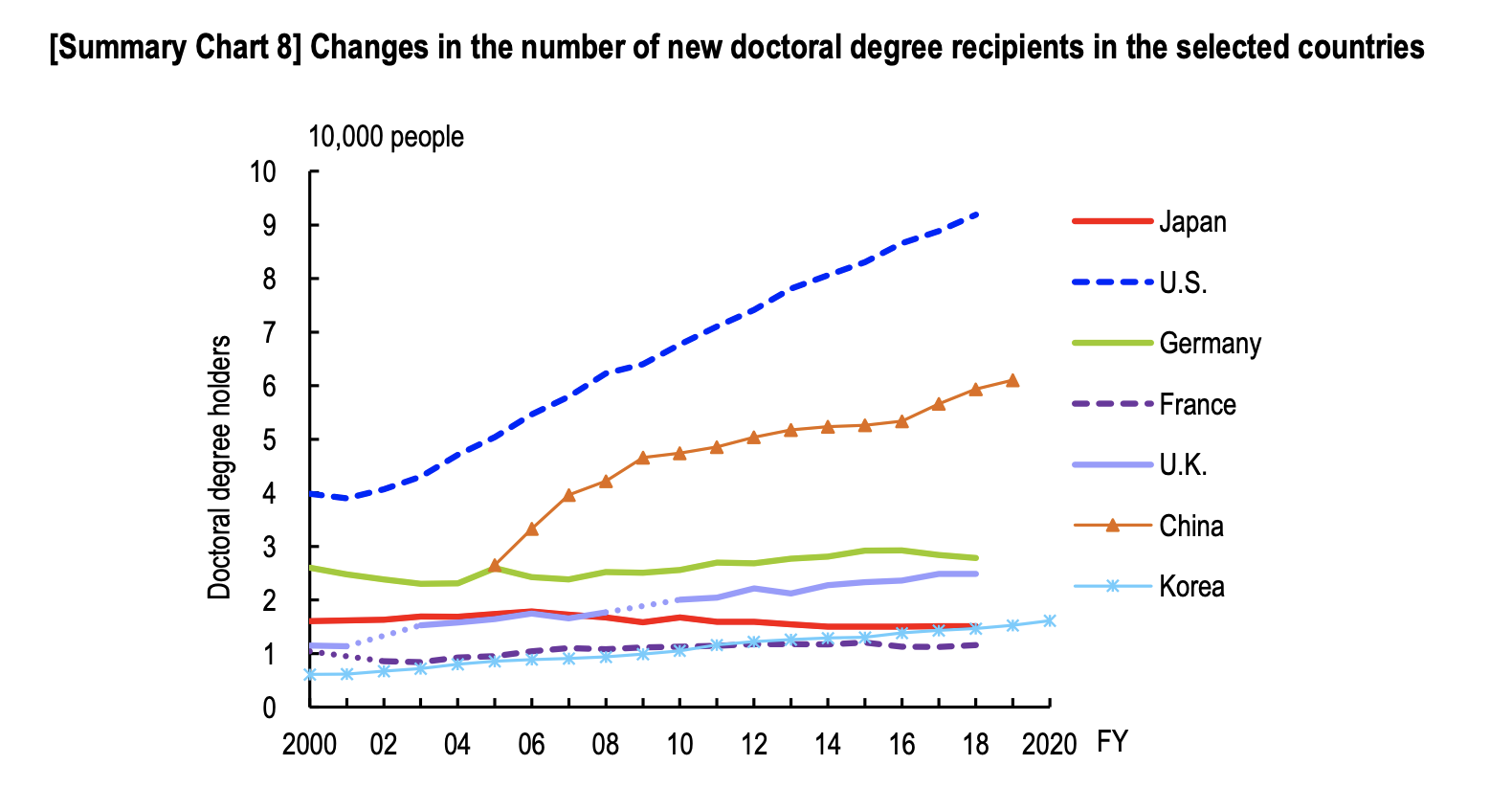

The above graph shows numbers of new PhD recipients per 10,000 people of some countries.

In Japan, the numbers of PhD recipients are slightly declining and now surpassed by Korea.

But I feel that the differece between the number of PhD students in Japan and those of western countries

are much more significant than the above data shows, at least in mathematics.

For instance, in 2020 there are around 20 PhD students working on the field of probability theory in Japan, but

I know more than 20 PhD students in that field only in Berlin.

The above graph shows numbers of new PhD recipients per 10,000 people of some countries.

In Japan, the numbers of PhD recipients are slightly declining and now surpassed by Korea.

But I feel that the differece between the number of PhD students in Japan and those of western countries

are much more significant than the above data shows, at least in mathematics.

For instance, in 2020 there are around 20 PhD students working on the field of probability theory in Japan, but

I know more than 20 PhD students in that field only in Berlin.

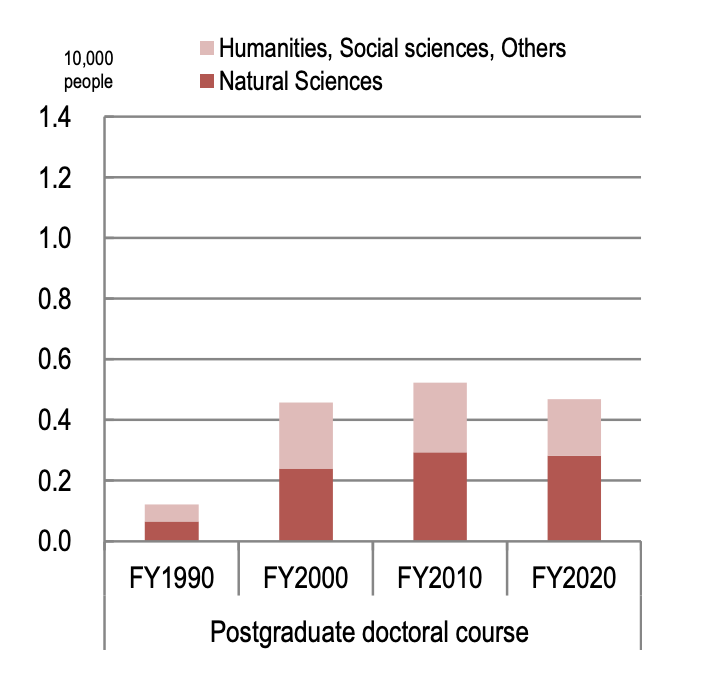

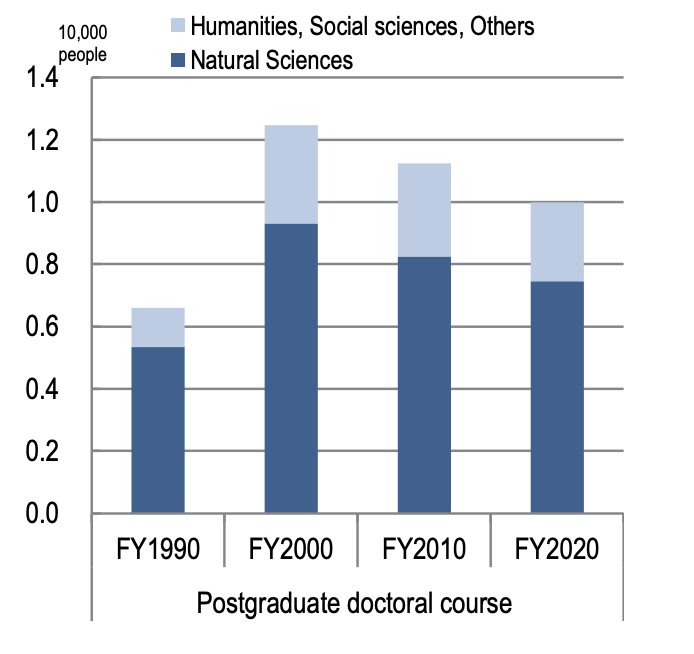

The above graphs show the number of female (red) and male (blue) PhD students in Japan. But in many fields of science including math, female/male differences should be much larger than shown in the graphs. Yet, this still seems to be a universal problem. For instance, among 16 PhD candidates from my research program, there are 4 female candidates. (Although the situation is much better than in Japan.)

Compared to western universities, the number of international PhD students is quite small. Unfortunately I could not find any data on it; this might manifest that people in Japan do not pay much attention to it. At the same time, I feel that it is a universal issue for non-western universities to attract strong international students. It is interesting to see if China can change the situation.

Why pursuing a PhD is hard in Japan

Now a question is why it is so hard to pursue a PhD in Japan. Here are my possible answers.

Lack of budget

Written later.

Evaluation of PhD recipients

Written later.

What will happen?

Written later.